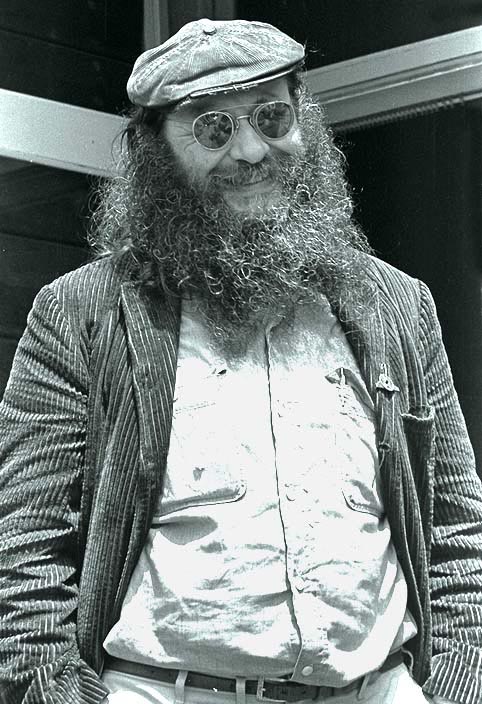

Photo by Robert Altman

< STORIES, ARTICLES, & RECOLLECTION

Berkeley Barb Dies, a Victim of '70s

by Paul Grabowicz / originally appeared in the Washington Post

(July 3, 1980) -- The Berkeley Barb, the notorious underground weekly that championed the era of student rebellion, LSD and changing sexual mores, quietly stopped publication this week, another Sixties symbol brought down by the Seventies.

Faced with a staggering deficit, dwindling circulation and a longstanding image problem the Barb 's owners have announced they are suspending publication "indefinitely." Insiders expect it will never be revived.

Since its heyday in 1969 when it was distributed worldwide and its readership topped 90,000, the Barb has been in decline. Current circulation hovered at barely 2,500 and weekly losses were about $1,500, according to sources at the paper. "For 10 years, these undergrounds papers have been dropping like flies, and the Barb was one of the last survivors," says Barb general manager Ray Riegert. "But the Seventies took over from the Sixties, and even the Barb became anachronism."

Nowhere has the shift in attitudes been more marked than at Berkeley, where 15 years a thriving population of hippies, bohemians, campus revolutionaries and dropouts gave birth to and nourished the Barb. Today, the nearby University of California campus is awash in apathy and the city's once proudly rebellious street denizens have become little more than the chronically unemployed.

"The only connection now between the Barb and the street people," said one former editor, "is they rip off copies of the Barb and burn them in trashcans in People's Park to keep warm."

The Barb was founded in 1965 -- the brainchild of Max Scherr, a Baltimore-born attorney who migrated West in the 1940s to join the Bay area's burgeoning bohemian community. In the beginning Scherr, a pixieish man now in his 60s who still gets his wardrobe out of free clothing boxes, put out the paper virtually singlehandedly, even hawking it on the city streets.

The amateurish, ink-smeared tabloid nonetheless quickly caught on with Berkeley's antiestablishment subculture.

Early headlines read, "One Hundred and Sixty Pigs Provoke Riot as Panthers Keep Cool" and "Crowd Mostly Right On." Its stories included the "exclusive" two-part series entitled, "I Was a Straightie" along with an announcement of a "Kiss In" to protest an arrest for lewd public conduct.

"It was a weird novelty," says former editor David Armstrong. "It was a hybrid of sex and dope and politics -- and all of that stuff was peaking at the same time."

The Barb was at its peak in 1969 when it ran stories advocating the formation of a "People's Park" on university owned land. In a bloody confrontation with police over the park, Barb staffers were shot, beaten and arrested as they freely mixed their rioting with their reporting.

But as quickly as it rose, the Barb fell, as the fervor of the 1960s diminished and the paper found itself clinging to a fading era. "Max [Scherr] was still back there plugging away, but there weren't too many other people still with him," says former editor Armstrong. "I mean how many times do you want to read about, 'Pigs Kill Kids'?"

Adding to the paper's problems was its sale in 1973 to International News Keyes, a subsidiary of Aruba Bonair Curacao & Trust Co., whose ownership remained a closely guarded secret by management. The sale bred paranoia in the Barb's staff.

Worse still, the paper's status with Berkeley's dwindling leftist community suffered as the Barb relied increasingly on sleazy sex ads for income. What once had been romanticized as the promotion of "free sex" became little more than thinly disguised advertising by prostitutes and massage parlors.

In a last-ditch effort at revamping the paper, the Barb in 1978 started what its staff dubbed "The Great October Revolution" by splitting the paper in two, spinning off the sex ads into a raunchy new publication called The Spectator. The Barb brought in a new editor and abandoned the strident tones of its revolutionary past in favor of feature stories and solid investigative reporting.

Quickly, however the "revolution" fizzled as the paper's ownership instituted severe staff cutbacks in the face of larger and larger losses. By February, the editorial budget had been cut nearly in half.

Later, the editor was fired and the publisher quit in protest, sparking feelings that the paper was quickly nearing an end.

The end finally came this week, with the suspension of publication. There is still the possibility the paper will be sold, but the chances are "remote," according to International News Keyes secretary-treasury Tom Meehan.

The Spectator, meanwhile, will continue publication.