ABOUT

Mission Statement and History - About Max Scherr - The Barb Bows Out

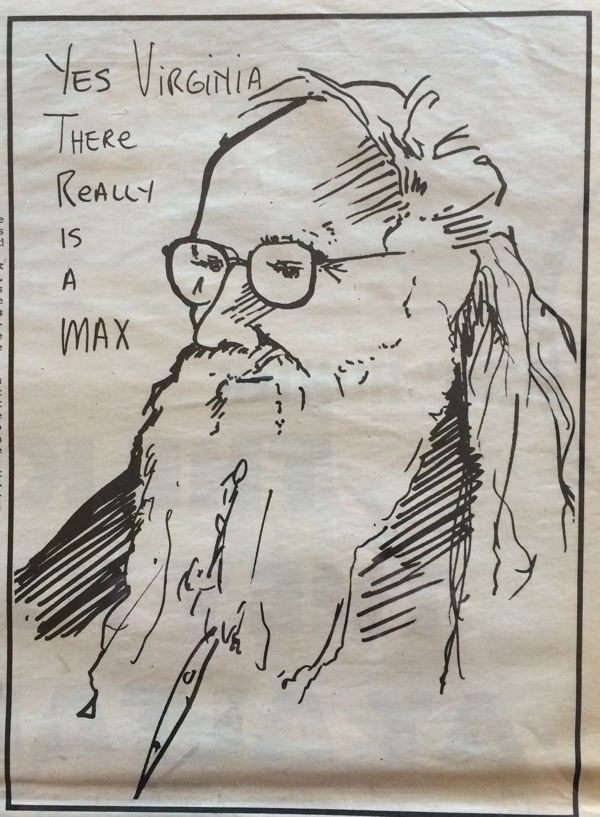

Max Scherr and the Berkeley Barb

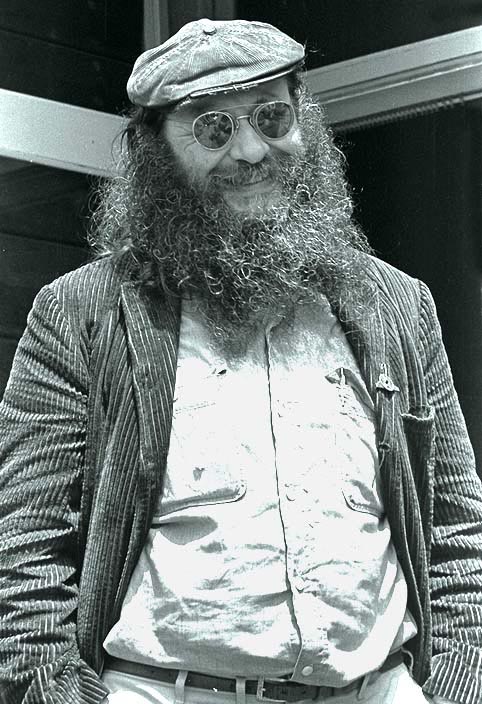

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1916, to Aron Sherker (later naturalized as Harry Scherr) and Minnie Linden Scherr, Max Scherr was a precocious student. He entered law school in 1935 and became a lawyer at the age of 21.

In 1940, he helped to organize the Transport Worker’s Union, which represented a couple of thousand taxi cab drivers and which, at the time, was the first desegregated and leftist political organization in Baltimore. As a result of his attempt to unionize local taxi drivers, his life was threatened and he was driven out of town by anti-labor goons.

At the age of 23, Max rode the rails westward to California and then hitchhiked south into Mexico where he met, fell in love with and, in 1942, married his wife Juana Estela Salgado, one of Mexico’s first female medical students.

In Mexico City, Max and Juana Estela Salgado de Scherr participated in the vibrant political culture of Latin American artists, leftist American expatriates, and European political refugees. However, in 1943, after hearing about the fate of Europe’s Jewry, Max enlisted in the U.S. Army. Max served under General George Patton and entered the European Theater of Operations in July 1944 as an Infantry Rifleman of the 175th Regiment, 29th Division. He followed the D-Day Invasion into Normandy, fought in the Rhineland, marched into Paris after the city’s liberation and served as a clerk and typist in the office of Marseille’s Provost Marshall.

In 1944, while Max was serving in the war, his wife, Estela gave birth to their first son, Sergio, in Mexico City. After the war, Max returned to Mexico, where he worked as a stringer for the UPI and a writer for

The Mexican Review.

In 1946, Max and Estela had a second son, Kolynos. Sadly, he died a few months after he was born.

Shortly after Kolynos's death, Max decided to move his family to the Bay Area where, in 1947, their third child, Raquel, was born. Unable to find work, Max took his family to Miami Beach, joining his brothers and sisters who had moved there from Baltimore. In 1948, Max and Estella's fourth child, Martin David, was born. That same year, propelled by his usual concerns with social justice and civil rights, Max helped to organize a march against the city's "anti-dark" laws (also known as "sundown" laws), which prohibited blacks from being in beach towns after sundown. (During WWII, the city's sundown laws also excluded Jews.)

In 1949, Max and his family resettled in Berkeley where he enrolled as a student at the university. Working at the Bancroft Library Max simultaneously pursued a Ph.D. in Sociology and studied for the California Bar Exam. However, in 1950, he was thrown out of school after refusing to sign the University of California’s mandatory loyalty oath. He ended up driving taxicabs to support his wife and three small children.

In 1956, Max landed a job with Bancroft Whitney, a legal publishing firm in San Francisco. He was fired a couple of years later for writing a lengthy entry for a legal encyclopedia on property rights in the south and their connection to the institution of slavery.

Max's life took a decisive turn in 1958 when he opened the Steppenwolf, a beer and wine bar on San Pablo Avenue that served Berkeley's burgeoning bohemian crowd. It was here that Max met Jane Peters, a young woman who became his partner and mother to two daughters, Dove and Apollinaire (Polly). Max and Estela never divorced.

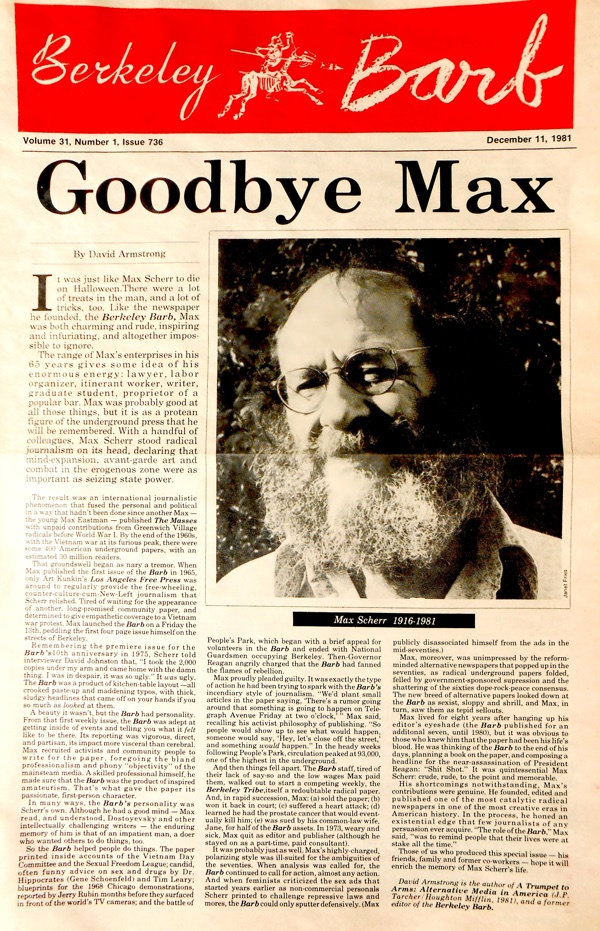

In 1965, Max sold the Steppenwolf for $10,000 and used the proceeds to begin publishing the

Berkeley Barb.

Fittingly, the logo Max chose for the

Barb (drawn by Oscar Zavala) shows a skeletal Don Quixote astride a skeletal horse armed only with a lance, whose tip is the Campanile tower on the Berkeley campus. Like Cervantes' crusading Man from La Mancha, Max was on a mission to right the wrongs of society, setting up clear expectations among his movement colleagues, the

Barb's employees and volunteers. Fueling those hopes, Max shaped the

Berkeley Barb into a popular alternative source of news and information reflecting the same views for social justice that he had long held. The writers and artists Max attracted covered civil rights, labor rights, and anti-war protests not as "impartial journalists" but as active participants –- a radical stance that uprooted the orthodox views of the traditional press. Once, when a young reporter asked for a press pass, Max famously replied: "If you have a press pass, you aren't a member of the Underground Press."

Max’s commitment to Leftist politics was well established by the mid-Sixties, although certain ethical questions arose from time to time when his belief in freedom of speech and press delivered some unexpected and unwelcomed consequences. In the case of the Berkeley

Barb, "freedom of the press" meant giving voice to untrammeled revolutionary critiques of Establishment values, but it also meant allowing more sexually explicit print and graphic content. Many saw the

Barb's advertising, some of its articles and cartoons, and especially the "personals section" (read "sex ads") as content that demeaned and exploited women. Max seemed wholly unprepared when the freedom of expression he nurtured in the

Barb later evolved into overtly sexist content, for which he was roundly criticized -- especially when it was discovered that he was reaping substantial profits from the

Barb's sex ads.

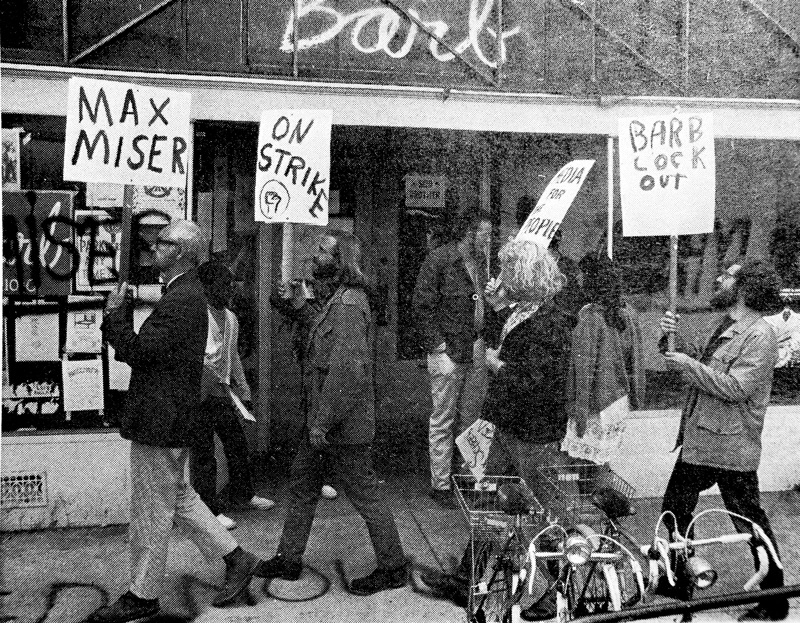

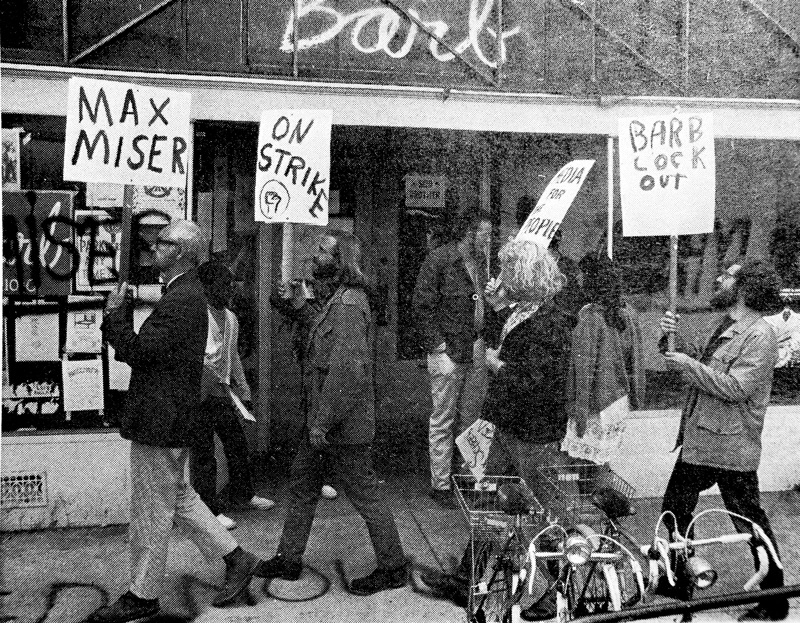

Max had led an austere life. He shunned materialism and imposed the same standards on those around him, but he did profit financially from the success of the

Barb. Several on his staff began to depict him as cheap for paying fledgling journalists meager wages and for complaining about the costs of basics such as pencil sharpeners. He was genuinely surprised and hurt when the staff, having discovered how much money the

Barb was generating, grew to resent Max's tight-fisted ways and organized a strike to protest his management. Most of the staff and volunteers eventually walked out and began publishing their own rival weekly, the

Berkeley Tribe.

Max was known as a fatherly figure to his staff, an earnest provocateur to his friends, and a dangerous radical to Governor Ronald Reagan and California's rightwing community. He was a man full of contradictions, aggressively fighting many battles (most of which have yet to be won) and refusing to compromise if it meant undermining the freedoms of the press -- even when those freedoms offended many. Over the years, the

Barb's content remained consistently radical and anti-establishment -- in seeming contradiction with the weekly's more sought-after explicit content. Max believed that censorship was far more harmful than any form of pornography. Over the years, arguments both for and against the use of different forms of sexual content would remain a volatile topic among the paper's staff and within its pages.

Many of the debates surrounding the feminist issues of the day became battles that were decided in courts of law. This was the case when Max and Jane ended their relationship. Common law couples like Max and Jane were forging new legal territory as alternative lifestyles like theirs became the new reality. Because Max and Estella never divorced, Jane lost her claim to common-law status. Max and Jane’s "divorce" pitted feminist lawyers and the liberal community against each other in an effort to define the new realities post-Sexual Revolution.

Max was one of many people trying to define the new morality of that age, but he tilted his lance toward the windmills more visibly than most. The

Berkeley Barb was a spur to action, providing a pointed argument to provoke debate, a poke in the eye to entertain the reader, and a thorn in the side to enrage the establishment. Max fought for his ideals with intelligence and vigor through the pages of his paper. He stayed on as the

Barb's Editor Emeritus until 1978. The

Barb printed its last issue in July 1980. Max died of cancer on October 31, 1981.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1916, to Aron Sherker (later naturalized as Harry Scherr) and Minnie Linden Scherr, Max Scherr was a precocious student. He entered law school in 1935 and became a lawyer at the age of 21.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1916, to Aron Sherker (later naturalized as Harry Scherr) and Minnie Linden Scherr, Max Scherr was a precocious student. He entered law school in 1935 and became a lawyer at the age of 21. In Mexico City, Max and Juana Estela Salgado de Scherr participated in the vibrant political culture of Latin American artists, leftist American expatriates, and European political refugees. However, in 1943, after hearing about the fate of Europe’s Jewry, Max enlisted in the U.S. Army. Max served under General George Patton and entered the European Theater of Operations in July 1944 as an Infantry Rifleman of the 175th Regiment, 29th Division. He followed the D-Day Invasion into Normandy, fought in the Rhineland, marched into Paris after the city’s liberation and served as a clerk and typist in the office of Marseille’s Provost Marshall.

In Mexico City, Max and Juana Estela Salgado de Scherr participated in the vibrant political culture of Latin American artists, leftist American expatriates, and European political refugees. However, in 1943, after hearing about the fate of Europe’s Jewry, Max enlisted in the U.S. Army. Max served under General George Patton and entered the European Theater of Operations in July 1944 as an Infantry Rifleman of the 175th Regiment, 29th Division. He followed the D-Day Invasion into Normandy, fought in the Rhineland, marched into Paris after the city’s liberation and served as a clerk and typist in the office of Marseille’s Provost Marshall.  In 1946, Max and Estela had a second son, Kolynos. Sadly, he died a few months after he was born.

In 1946, Max and Estela had a second son, Kolynos. Sadly, he died a few months after he was born.  In 1956, Max landed a job with Bancroft Whitney, a legal publishing firm in San Francisco. He was fired a couple of years later for writing a lengthy entry for a legal encyclopedia on property rights in the south and their connection to the institution of slavery.

In 1956, Max landed a job with Bancroft Whitney, a legal publishing firm in San Francisco. He was fired a couple of years later for writing a lengthy entry for a legal encyclopedia on property rights in the south and their connection to the institution of slavery.  Max had led an austere life. He shunned materialism and imposed the same standards on those around him, but he did profit financially from the success of the Barb. Several on his staff began to depict him as cheap for paying fledgling journalists meager wages and for complaining about the costs of basics such as pencil sharpeners. He was genuinely surprised and hurt when the staff, having discovered how much money the Barb was generating, grew to resent Max's tight-fisted ways and organized a strike to protest his management. Most of the staff and volunteers eventually walked out and began publishing their own rival weekly, the Berkeley Tribe.

Max had led an austere life. He shunned materialism and imposed the same standards on those around him, but he did profit financially from the success of the Barb. Several on his staff began to depict him as cheap for paying fledgling journalists meager wages and for complaining about the costs of basics such as pencil sharpeners. He was genuinely surprised and hurt when the staff, having discovered how much money the Barb was generating, grew to resent Max's tight-fisted ways and organized a strike to protest his management. Most of the staff and volunteers eventually walked out and began publishing their own rival weekly, the Berkeley Tribe.